Flood & Fire in the Studio

Flood and Alan Moulder teamed up for the first time in years to produce Foals’ Holy Fire, and turning the dynamic duo into a trio was Aussie engineer Catherine Marks. The sessions turned Assault & Battery Studios into a hands-on experimental lab, and everyone had their hands in.

Exactly how British rock band Foals managed to go from almost complete unknowns in Australia to topping the ARIA chart earlier this year with their third album, Holy Fire, is a bit of a mystery. The many enthusiastic local reviews provide a clue, but particularly notable is the credit many reviewers give to the production, writing things like, “the album sounds a million bucks,” “despite the wide-ranging sounds, tones and influences on this album, Holy Fire hangs together perfectly, thanks in large part to great production,” and, “if this album doesn’t sound amazing at full volume, tearing down the street at night…” It’s rare for mainstream reviewers to comment so extensively on the production, but one listen to Holy Fire immediately reveals that the band’s angst-ridden vocals, and ultra-tightly played rock arrangements are stirringly augmented into a wild cocktail with all manner of loops, synth sounds, and other sonic landscaping, making it an immensely impressive-sounding record.

Responsible for the production aspect of Holy Fire were legendary British mixers and producers Flood and Alan Moulder. The former has worked with U2, Nine Inch Nails, Nick Cave, and PJ Harvey, while the latter is known for his achievements with Depeche Mode, Erasure, Foo Fighters, and Led Zeppelin (he mixed the recent Celebration Day DVD/CD). A crucial role in the way Holy Fire sounds was also played by Australian Catherine J Marks, who engineered the entire album, and who has in her relatively short career already built up a respectable set of credits, including Futureheads, Goldfrapp, PJ Harvey, and Placebo. Marks gained many of her earlier credits in working with Moulder and/or Flood, as the two mentored her (see sidebar for more details about her), so it’s easy to see how she ended up working on the Foals project.

AUSSIE CONNECTIONS

Holy Fire’s Australian connection is further strengthened by the fact the band spent the beginning of 2011 working in Sydney with Jono Ma, guitarist and keyboardist of Sydney band Lost Valentinos and his own project Jagwa Ma. The band reportedly went back home with stacks of loops, samples and grooves that supplied a “foundation to the new record,” according to Foals keyboardist Edwin Congreave. Foals must have felt they needed the help of some world-renowned, dyed-in-the-wool professionals to take things further, because they once again turned to Alan Moulder, who had mixed their second album, Total Life Forever (2010), with assistance from Marks. Flood and Marks take up the rest of the story of the making of Holy Fire. On the phone from Los Angeles, Flood recounted…

“I’ve long had Foals on my radar, so when Alan asked me whether I fancied doing the production together, it seemed like a really good idea. The two of us do projects together once every five or six years, and it’s great because it pushes both of us. The band had been sending us song ideas over the summer, and during the last months of 2011 and early 2012, Alan and I repeatedly went over to their rehearsal studio in Oxford to work on these. The idea of this pre-production period was to put all ideas on the table, no matter whether it was just a riff or a fully-formed song, and give them the right feel and groove, arrangements, structures, key, tempo and so on. Some songs fell by the wayside and others came to the fore during this process, and we ended up with about 15 strong song ideas. There was a laptop with Logic and Ableton in the room, and three microphones that were pointed roughly in the direction of the band, just to document what they were doing. For Alan and I it was important to get a sense of how they played together as a band, find out how everyone felt about the songs, and establish a chemistry between everyone. Before walking into a studio that costs a lot of money, it’s important to make sure the chemistry works!”

ASSAULT & BATTERY

The actual recordings for Holy Fire took place in Flood and Moulder’s studio, beginning March 2012. Since 2008 the producers have been running a studio complex in north-west London, Assault & Battery, with Moulder predominantly residing in the downstairs mix room, Studio 1, and Flood taking care of the upstairs Studio 2. Recordings for Holy Fire took place in Studio 2, which is one of the UK’s prime tracking facilities and sports a 77m2 live room with two sizeable booths of an additional 30m2 each, and a 36m2 control room with a Neve VR60 60-channel console with flying faders.

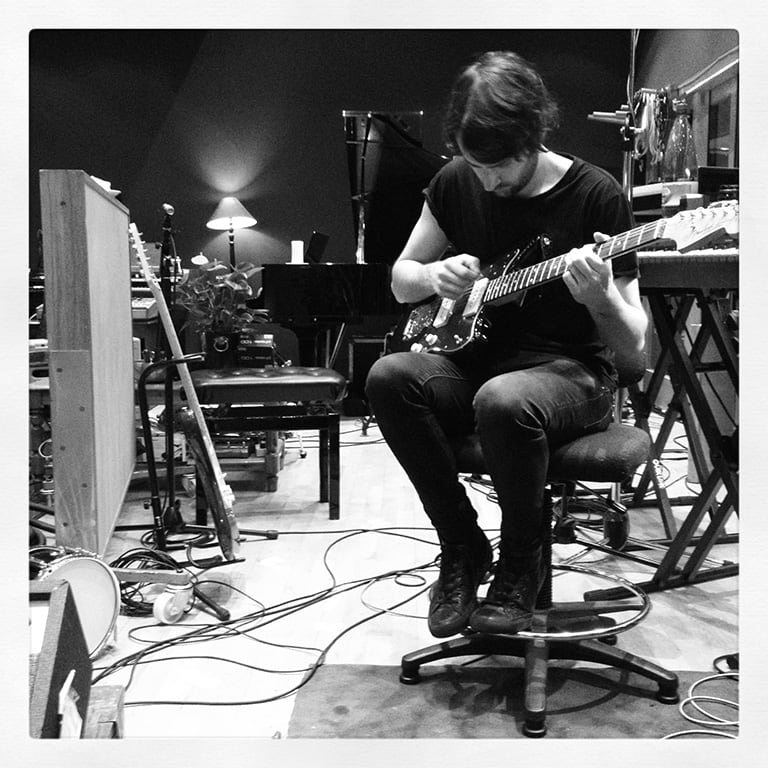

The live rooms are full of all manner of musical instruments, including synths, keyboards, and amplifiers, aimed at making it a very creative place for musicians. With the downstairs studio an ideal place for programming, mixing and additional recording, Moulder and Flood had everything in place to successfully conduct the Foals album sessions, but they still felt they could do with some help.

“Although Alan and I both engineer, we wanted to have someone who could do all the engineering for us, so we didn’t have to think about that, and could focus fully on the production side,” explained Flood. “We decided on Catherine, because she’s an amazing engineer with great ideas, and the other thing is that she’s a woman and could balance the nine-man strong male energy in a room with five band members, two producers, and two assistants. She listens to things and approaches things from a female point of view, and the way she will balance a song, or just her take on the way a certain version of a track feels compared to another one, is just different. To have the opinions of a woman coming in all the time was invaluable. I mean, we’re making music for men and women, so you want to take all viewpoints into account. Catherine also recorded most of Yannis’ [Philippakis] vocals. Because he will interact differently with a woman than with a man, this of course affected his performance, as it would do for every singer.”

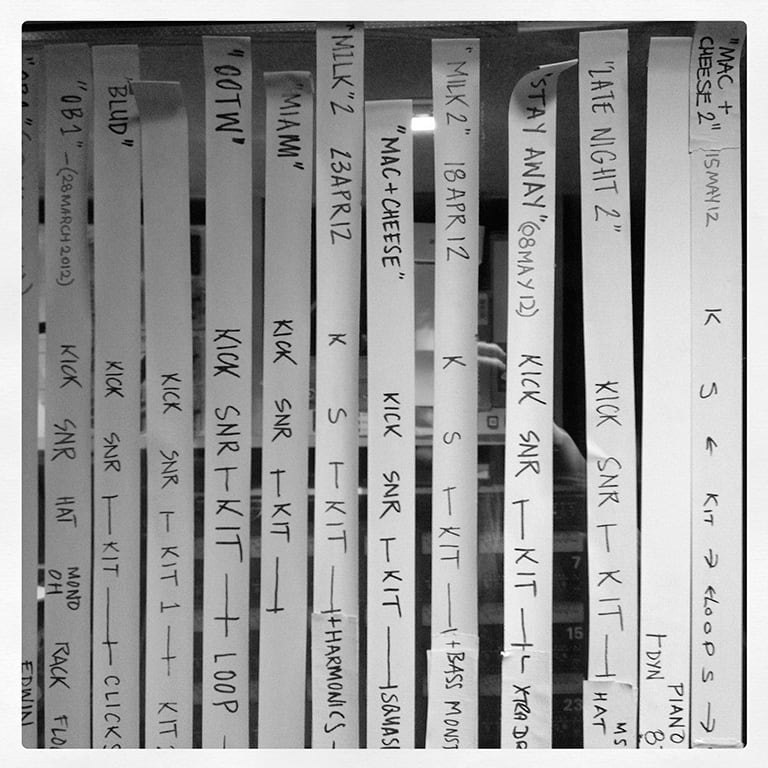

DUPING YOUNG FOALS

Marks: “We began recording on March 12th, and took a break for 10 days in April, and then came back, and worked until proper mixing began in August. Prior to recording we spent time thinking about how to arrange the layout of the live room and where to position each member of the band. This was crucial as we wanted to be able to not only have the ability to record the band in the same room, but also to have the potential for separation should we need it. Each band member had their own area with their own workstation and pedals and amps, and we also had a small PA in the room through which we played back a kick drum, or a bass, or a loop, or whatever. It took about three days to set up the room, and we decorated it with tropical plants and rugs and there was lots of lighting. It looked amazing, like a jungle. During the first two weeks of recording we told the boys that we were only demoing the tracks, and were not really focussing on getting actual takes, and this meant that they were a lot more relaxed while they played together. There was no red-light fear, so the energy was more natural. The band has mentioned they felt they had been ‘hoodwinked’ by Flood and Moulder — but they knew what was going on.”

Flood: “It wasn’t a deliberate decision to effectively dupe the band, but Alan and I were very conscious they had had difficult experiences during recording in the past, and so we thought it’d be really good if they didn’t feel the pressure of the red light being on. Setting up took quite a long time, two to three days, so once everything is in place and mic’ed up, you pretty much record everything anyway. But we suggested to them to do some demos of songs that were already pretty well-formed, which meant that there was none of the freaking out and getting overly tense that often happens when the red light goes on and can really affect performances. After a couple of weeks they had laid down most of three or four tracks, and after that they were so comfortable with the process it didn’t matter that we were now formally going for so-called ‘proper masters’— it was just an extension of what we had already done.”

HANDS IN, HANDS ON

Duping the band into thinking that only demos are recorded will only work so many times, but it does reflect a principle that every good engineer is aware of, which is to be ready to record before the artist or band expects it. In this case, getting the feel factor right was especially important, because, despite the fact Holy Fire sounds awash with loops and post-production textures, both Flood and Marks stressed that the band played a large proportion of the album together live in the studio.

Flood elaborated, “I’d say that the backing tracks for the majority of the songs on the album were played live, and whenever they played together we aimed to keep all the backing tracks, not just the drums, or the drums and bass. For most of the time we also tried to keep the guitars and the keyboards. One thing that bands always ask in the studio is why they never sound the way they do live, and this tends to be because the process is so different. In this case we really wanted to get the energy of the band playing live and start layering and crafting after that, looking at parts that maybe don’t quite work, adding overdubs, and adding vocals. This meant that there were often many different rooms with people working, Alan might be off downstairs working on a mix or on guitars, I might be in another room doing sonic treatments, vocals were going on all the time, other people might be working on other songs, Edwin would be doing stuff to tracks and was at times almost remixing them and we’d then bring what he’d done back into the main session.”

This seemingly manic approach of all-hands working all the time, was facilitated by Marks’ split setup: “I had the Neve VR60 desk set up with the mic channels on the left, and monitoring on the right, so Flood or Alan could be over on the right if they needed to do things while recording. I set up everything knowing that when working with Flood and Alan things can change at any moment. I had to be prepared for 100 different scenarios. We had two different drum kits set up, one with its own little drum house, surrounded by baffles, and we hung a leopard print rug over the top and put some flashing lights in there. We also had a drum kit set up in a separate booth, which we called the dull kit, or the close kit. Jack [Bevan], the drummer, had headphones on, through which we usually played a click, and the others also had headphones on if they wanted them. There were amplifiers in the main live room, as well as in the booths, so we had the option of separation if we wanted it. But the idea was that spill would be part of the live takes. I don’t think we ever had problems with it. It just added energy to the songs.”

CALLING MY NUMBER

My Number, the catchy second single off Holy Fire, combines influences from Rick James-like eighties disco, Talking Heads, electro, and 21st century alternative rock, if such a thing is possible. Marks highlighted a few of the pieces of kit she used during the session: “I used a lot of outboard to record the drums, including Alan’s new Helios mic pres on the kick, snare and overheads, as well as Trident mic pres for the floor and rack toms, a Summit, and the Neve 1073, amongst other things. But everything could change very quickly. Assault & Battery contains so much amazing gear that Flood and Alan have amassed over years and years, it’s hard not to want to try everything! I felt like Indiana Jones going into the archives sometimes when looking for gear, because there are so many foreign pieces of kit from so long ago. That was really exciting. On the kick I often used the Beyerdynamic Opus 65 microphone, which is another one of Alan’s, a Neumann U47 at the hole and a Yamaha NS10 speaker mic outside, and I also often used a C-Ducer contact mic on the rim. The snare often had Shure SM57s top and bottom, a Neumann KM184 on the hi-hats, overheads were a mix of Neumann M7, Coles 4038, and perhaps a couple of Shure SM57 microphones, and the toms had Sennheiser MD421s on them.

“One of the most important ingredients for the sound of the album became a Shure SM58 hanging from the ceiling, which was initially used for foldback. We squashed it to pieces so we could hear what the guys were saying, and in the end we used it constantly in the mix. It sounded great, pumping and glueing everything together. We also had another four room microphones scattered around that were used most of the time, and a Neumann KU100 binaural dummy head. On the bass I used a DI and a Neumann U47FET on the cabinet, both going through the Chandler TG1 mic pre, the DI through an Empirical Labs Distressor, and the amp channel through an Inward Connections Vac-Rac TSL compressor. The guitars also had a DI, and I had an SM57 and a Sontronics Delta ribbon mic on the cabinets. I had all the microphones, apart from the drums, coming up on the Neve desk, whether they first went through a mic pre or not, and used the desk as a gain control for the levels that went into ProTools. In addition there were Yannis’ vocals, which were recorded with a Shure SM7B, going through a Neve 1073 mic pre, and then a Distressor. The SM7B has a pop shield that he could play around with for a slightly duller sound. We split the vocals so they were also going through an effects pedal which he could control. The effects were monitored via a Maestro amplifier that we had placed in front of him. It is something that looks like it’s from the ’50s or ’60s, but Flood says he bought it at K-Mart. We put an AEA R84 ribbon mic on the Maestro to get that crunchy, dirty vocal sound. And we used a U47, the R84 or an SM58 on backing vocals. To be honest, it was whatever was there and ready to go!”

To have the opinions of a woman coming in all the time was invaluable

MAKING HER MARK

Say you have a well-paying creative job at a respectable architecture firm in sunny Australia, with a team of people working for you, and a bright future ahead of you. Surely, the last thing on your mind would be to leave that job, move to grey and grim London and start a job that involves sitting in the back of the room for most of the time, not speak unless spoken to, and being paid a pittance? For most people it’s a no-brainer — that is, ‘No way!’ — and yet it’s exactly what Catherine J Marks did. Growing up in the Camberwell area of Melbourne, she learned to play classical piano and had dreams of being a pop singer, but chose to study architecture at Melbourne University. As part of her degree Marks was required to do work experience, and decided to do it in Dublin, Ireland, because her mother is Irish. One night, at a Nick Cave concert in Dublin, she met a certain Mark Ellis, completely unaware that the man was a famous producer, better known as Flood.

“We started chatting and became friends. I knew he was a producer, but still didn’t quite understand how significant his role in the music industry was, and at my going away dinner I jokingly suggested that he should produce me. He said, ‘No, but if you want to work in the music industry, I suggest you go back and finish your degree, and we’ll see what we can do.’ Flood recalls, “She didn’t really want to finish her degree, but she did and after that came over to London, in 2005, where I employed her at the studio I had at the time in Kilburn (north-west London). When Alan and I took over Assault & Battery in 2008, she moved there with us.”

Marks must have had some second thoughts about stomping off abroad to an uncertain future, because after completing a Masters in Architecture she did work for a year at architecture firm H2o in Melbourne. But eventually she followed what she regards as her true calling. “I didn’t have any aspirations anymore to be on stage, but I really wanted to become an engineer and a producer, and the more people said I couldn’t do it, the more I wanted to prove that I could. But when I came over to London, I really had to change my personality, learning to be invisible and being a support. I was quite a bubbly person, and learned to rein that in, and I also started to dress very conservatively, almost like a boy, and also cut my hear very short, all because I thought it’d be easier for me to fit in.”

DRESSING DOWN

It seems crazy that Marks would have had to repress her femininity to fit in, but demonstrates the conundrums faced by women trying to fit into an almost completely male-dominated studio world. “It’s a really sad situation,” commented Flood. “Because I think that when albums are made with a balance of male/female energies, you make better records. I really think that music in general could take a massive leap forwards if women were more involved in the process of recording and producing it. I don’t know why there are so few women working in studios. Sometimes I wonder whether it is because the process of getting there is so male. It’s quite difficult for women to break into the studio world, and then to be part of the process and be comfortable being a woman at the same time. Catherine has managed that.”

Marks concurred: “Studio life is definitely all-encompassing and can mean that other aspects of your life have to fall by the wayside. You have to be prepared to make sacrifices. Days can be very long and weekends non-existent, especially when you’re first starting out. It also requires a certain amount of maturity and tolerance. I didn’t start until I was 25 and I now know I would not have coped at 18. I think it’s not really about whether you are a male or female in the studio, everyone has something different to contribute, but more about whether you are prepared for the commitment. Flood and Alan have always told me that it’s an asset to be a female engineer, and I learned to embrace that. Initially I felt that I had to work harder than my peers, but these days I get asked to do sessions where people feel that the artist needs more time and attention, and I guess I’m more tolerant of that. So it’s totally not a problem now.”

MIX EXPANSION

Since 2010 Marks has been working as a freelancer, and she has also been expanding her work into mixing and producing. Her credits over the last few years include Editors, Ian Brown, Placebo, Shakira, PJ Harvey, Depeche Mode, Death Cab For Cutie, Killers, and many more. To accommodate low-budget projects, she’s even gone as far as to mix some projects on her laptop. She explains, “The projects I mixed on my laptop were Duke Spirit, We The People, and Matthew Mayfield. I did this on my MacBook Pro, ProTools 9 and just the standard laptop soundcard, and listened back via my Sony MDR7506 headphones and M-Audio AV40 or Genelec desktop speakers. It’s not something I particularly enjoy doing, although I am really proud of what can be achieved with these limitations, it’s really out of necessity when there’s no budget. I much prefer working on a desk, and with proper monitors, my favourites being Unity Audio The Rock monitors, M-Audio DSM2s, I also have some baby Genelecs, and I love Alan’s ATC SCM20s.”

In recent years, Marks has also finally managed to make another dream come true, which is that she now regularly comes back home to her native country to work with Australian acts. “That actually took ages to happen,” said Marks. “Initially I thought that I’d go to the UK and learn everything there is to know, and then I’d go back home and work with Australian artists. And I did keep coming back and having meetings, but something wasn’t connecting. But the moment my career in the UK took off, I got interest from Australia, and I now regularly go back. It means I have the best of both worlds. I do regard London as my home now, though. And yes, I have long hair now. I’m fully back to being me!”

OUT OF THE BOX BOXES

Marks’s recording setup for Holy Fire is one factor in the album’s gorgeous, multi-layered, and full-on sound, but both she and Flood emphasised that the mainstay of Holy Fire’s imposing sound came from getting the sounds right at source level, and using a plethora of out-of-the-box, erm, boxes. Flood: “The ideas for adding textures came during the time at Assault & Battery. Foals are not a straight rock band, and they were really into experimenting with sound. These explorations were for the most part exclusively done out of the box. I hate using the word ‘organic’, but it was a fluid process, involving the musicians at every stage. They would play together, and then they’d build loops upon loops, mostly using sequencers and pedals, often from Line 6, and they’d use synthesisers to create all sorts of textures. I have a Roland System 700 in Studio 2, which I use mainly as a giant effects unit, and there were times when we decided to shove everything through the System 700. Jimmy [Smith, guitarist] also really loved the Sequential Circuits Pro 1, and we used quite a bit of the old Roland Vocoder. Edwin did quite a lot of stuff with soft synths in Ableton, which we then processed outside of the box, or tried to mimic with the MiniMoog or pedals, things like that. Then somebody might go off and do a lot of looping and editing in another room, and we might then reconvene and play it as a complete band, taking the information from a loop, but not using that loop in the track. For Alan and I this process was a huge bonus because it meant that we could explore new options, and not do what everybody else does.”

“This experimental aspect was really exciting for me,” said Marks. “We’d record the band then have a break, and Alan and I would be in the control room and say, ‘let’s process something, what should we try?’ We’d spot something in the room and say, ‘OK, let’s try this!’ Whether it was processing a kit through the Korg MS20 or Time Mod, or running a guitar part through the Eventide H910. It meant we were responding to what had just been recorded. I think the boys had saved some loops from the Jono Ma sessions, but a lot of the stuff was created and manipulated in A&B. I’d never thought about the record containing many loops, because I just considered them as other instruments. It was an element the band responded to. Everybody was constantly working on and coming up with things for the band to respond to and many of the songs had two or three versions before we settled on a final shape. I recorded the loops direct into ProTools as well as putting them through amplifiers and the PA and miking them. I’d go into the archives and get boxes out, like Alan’s new Marshall Time Modulator or the Voodoo-Vibe by Roger Mayer, which sounds the way it looks: chunky and dirty. We also used the Eventide H910 Harmoniser a lot. Flood would often go off to another room and work on loops and textures — we called it ‘wormholing’ — where he’d spend hours programming his Roland System 700 or the ARP 2600 modular synth and would come up with something that made the track infinitely better. Alan tends to be more on the board, and would spent a lot of time tweaking sounds and balances that improved things and provided new inspiration. The band was incredibly motivated and each one of them was always doing something. This was probably the first session I have worked on where there was no sitting around!”

Flood: “Alan’s strength lies in his ability to refine and craft the raw energy of the backing tracks, where we often joke that I am quite happy to leave all the microphones open, use monitors, have the PA to 11 and everything bleeding into everything else. But he hates that kind of thing! He likes to be really precise about how it sounds. So we often have a labour division where I can set up the live room the way I want it, while he looks after how it is recorded, in this case together with Catherine, so he can get the level of precision he wants. Generally speaking I was in the live room guiding the band with performances while Alan was in the control room, and once we had enough backing tracks, he’d go and do some trial mixing downstairs to try to get inside of the sounds and work out what parts were and weren’t working. Sometimes we’d swap, with him going upstairs and recording overdubs and me doing some mixing and refining. Meanwhile Catherine was holding the ship steady.”

STRINGING ALONG

In addition to all these extraordinarily industrious-sounding goings-on, there was also a last-minute decision to add some real strings to some of the tracks. Marks has the low-down: “They were also recorded at A&B2. The band was still around, so they had to clear the room. We had about 12 players in the room — two double basses, two cellos, four violas and four violins — and used so many microphones to record them, it was ridiculous. I felt that we were using too many, and I knew which ones we’d actually eventually use, but it was an exercise in making sure nothing went wrong and that we captured everything, because a string session is typically quite expensive and you have a relatively short time to record the players. All close mics were Neumanns, with U47s on the basses, M93s on the cellos, and M7s on the violas and violins, and for room microphones I used Coles 4038, Neumann M55K, and AEA R84 ribbon microphones — pretty much every mic that we had. The string players were incredible, and they played great parts, but once they were in the studio, everyone got very excited about making them do things that didn’t necessarily sound like a traditional string section, such as making the strings sound like bumble bees or seagulls. Hugh Brunt had done the string arrangements, and Yannis was also quite vocal about trying these different sounds.

“We did rough mixes throughout the entire recording process, usually at the end of the week, whoever was at the desk would get all the tracks up, and Alan and I would balance them partly in ProTools and partly on the Neve desk, so everybody could make decisions on what they were happy with. But we were trying not to be too precious about it. As the sessions progressed, more and more balancing took place inside the box. Once we had done the bulk of the recordings, Alan moved downstairs to do rough mixes, so the band could focus on recording vocals. I actually recorded the vocals in three rooms; I started upstairs in A&B2, and then moved to a side room in Studio 1, and then during the very final weeks both studios were booked, so we moved to Flood’s house for vocal recordings. We spent a good month just recording vocals. Yannis likes to craft his lyrics, and for him it’s more about how they sound than how they look on paper, so he had to sing them to be sure that they worked. It was quite fascinating.”

FLUID FLOOD & MOULDER

Flood: “Some songs took a long time to come together. Inhaler, for example, was one of the songs that they had worked on in Australia. It had been around forever, and just wasn’t happening. Then one afternoon we were trying out some different ideas, and everything suddenly slotted into place and it worked. We tracked it straightaway and Alan went downstairs and mixed it. He didn’t do a final mix, it was just a matter of making sure it had the right feel. In this process, mixing was almost like another instrument. There are very few overdubs on Inhaler, in contrast to My Number, which was one of the songs that was the most fully-formed. They played it to us in their rehearsal space during pre-production, and it was immediately obvious to Alan and I that it’s an amazing song. But a song like that can run a fine line between being a bit lightweight and having real integrity and depth about it. Alan and I knew that it would be the hardest song to get right, and we tried loads of different ways of doing it. We spent a lot of attention in the detail and really pushed that song to its maximum, so now that every time that song is played, everybody goes: ‘This is great!’

“Proper mixing for Holy Fire began in the last two weeks of August,” explained Marks. “And then we took a month off and finished mixing in October.” The final mixes took place at Assault & Battery Studio 1, on a 72-channel SSL SL4072 G Series with G+ computer (the desk in fact has 24 E-series channels and 44 G-series channels), with Moulder manning it for most of the time. Flood: “Yeah, the album was predominantly mixed by Alan, but there were a couple of songs where he said, ‘I can’t get inside of this, can you have a go?’ Things were very fluid, as they had been during the entire recording process. We were trying things all the time, and sometimes it felt as if we were going round in circles, but as long as everyone was on top of things, we always ended up in a better place.” Marks: “We had to be prepared that with all this experimentation not everything was going to work. But ultimately we were all on board with whatever needed to be done, because we all had the same goal: To make one hell of a record!”

RESPONSES